Dexter Frederick, MD, remembers the exact moment when he decided to become a physician. Following a flag football injury he received as a young high school student, Frederick found himself enchanted by the healthcare team bustling about the ER.

“The doctor came in,” Frederick tells Medscape Medical News, “sat me down, and showed me the X-ray of my knee. I was blown away. I was entranced by the film he had in his hands, to see my actual body reflected on the screen — it stuck with me. This doctor looked like me; I could relate to him. I was fascinated.”

Dr Dexter Frederick

From that moment forward, Frederick did everything he could to achieve his dream of becoming a doctor. “It empowered me to seek mentors,” he says. “To take CPR classes in high school, to shadow doctors.” He later earned his undergraduate degree in Respiratory Care from Columbia Union College and his MD from Loma Linda School of Medicine, specializing in internal medicine.

“It wasn’t all smooth sailing, of course,” he says. “I struggled a lot with some classes in medical school. It wasn’t until we were taught about memory and just how powerful of a tool it could be that I was able to figure some stuff out.”

Frederick held on to this idea of training your memory and vowed that, if he ever got the opportunity, he would teach students how to make the best use of their memory. In 2003, that dream became a reality when the Brain Expansions Scholastic Training (B.E.S.T.) Medical Academy enrolled its first class of 15 kids.

The Tampa Bay-based B.E.S.T. Medical Academy is a series of programs designed to give underrepresented and disadvantaged youth the support they need to succeed.

“When I moved to Tampa and started working in an underserved clinic,” Frederick said, “the kids there with their parents would tell me ‘I want to be a nurse’ or ‘I want to be a doctor’. So I would ask them ‘Do you know any nurses? Any doctors?’ and they always said no. That’s when I realized just how big that void is.”

Just like the ER doctor who treated his knee all those years ago, Frederick recognized that his presence in the clinic had the potential to inspire others to pursue medicine. “I tell everyone that the B.E.S.T. organization is a reflection of my journey,” he says. “There are pieces of my journey incorporated into different aspects of the program. It worked for me so I knew that it would work for students, too.”

Beyond assisting elementary, middle, and high schoolers with afterschool tutoring and medical-adjacent activities, B.E.S.T. operates a variety of programs, including a Summer Medical Academy where teens learn directly from healthcare professionals in clinical settings, and the Memory Training Program, which teaches effective study skills for students, and more.

Beyond offering educational opportunities, B.E.S.T. places an emphasis on providing mentors for young people interested in healthcare.

Dexter Frederick, MD, sits with fellow B.E.S.T. leaders at a White Coats ceremony for 5th graders graduating from the program.

“We are all about trying to push those underdogs,” Frederick says. “Those students who thought about entering the medical field but didn’t have the guidance or support to achieve it. It is known that if a basketball player, a great pianist, a journalist, becomes a parent, their kids are more likely to be successful in that particular field if they choose to go into it. They know the journey, the hiccups, the network.”

“That’s what we try to create for students of color. We want to give them the father or the mother or the brother or the sister in the healthcare field that they never had. We make these mentors available for these kids along their journey.”

From Underdogs to Advocates

Sophia Diaz, a B.E.S.T. graduate, is grateful for the resources the program provided for her. Currently, she is in the process of applying to physician assistant school. So far, she’s had one acceptance.

Sophia Diaz

“I come from a family of two immigrants,” Diaz says. “My mom is from Puerto Rico and my dad is from Cuba. No one in my family works in the medical field and I was the first to pursue this career. I felt like an underdog going into this because I didn’t have as many resources as someone else may have had.”

Through B.E.S.T., Diaz was able to shadow different doctors and healthcare professionals, building up a network of resources that she may not have had otherwise.

“I struggled with some classes in college,” she says. “But I had these lessons from the B.E.S.T. program that I used, the biggest one being don’t be afraid to reach out for help — your teacher, your school, your peers. Do what you can to help yourself. Ideally, people want to do it all on their own but it’s just not possible. You can’t do it [all] on your own and somebody may have advice that you’ve never thought of and perhaps you’ll be able to help that person as well.”

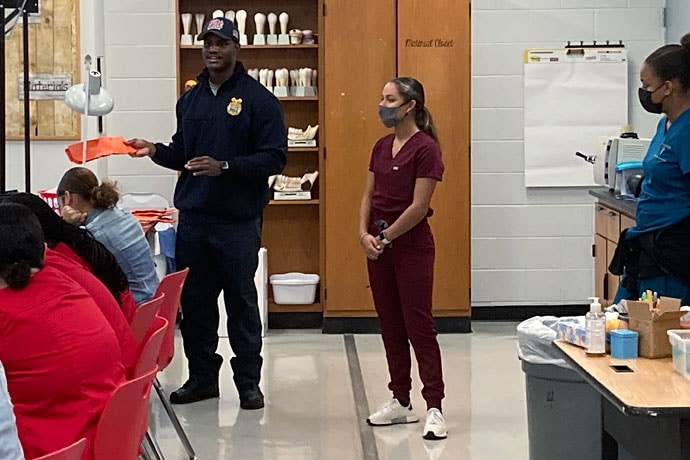

Sophia Diaz, along with a fellow mentor, speaks to a middle school class.

Additionally, enrolling in the B.E.S.T. program gave Diaz the confidence to not only pursue a career in medicine but also to advocate for herself and people like her.

“In one of the shadowing experiences that I did during a summer program, I was in the ICU following some RNs during their rounds as they checked on patients,” she says. “We came across a Hispanic family that didn’t speak any English and the nurse didn’t know any Spanish. I remember seeing the family struggle, that the nurse was doing something that the patient didn’t want. I was just a 17-year-old girl but I knew exactly what was going on. I ended up being the mediator in that situation and was able to let the nurse know what the patient wanted.”

Diaz says she’ll never forget that moment: “I was able to use my culture and my bilingualism to help a patient. It’s important that I’m bilingual and Hispanic because when I do become a provider, I will be able to communicate with those patients and I will understand them on a different level.”

Darrys Reese, another B.E.S.T. graduate, works as a medical pathway coordinator alongside Diaz at B.E.S.T. The program’s coordinators work one-on-one with students as well as help organize after-school activities and guest speakers.

Darrys Reese

“Honestly,” Reese says. “My parents kind of forced me into the program. They knew that I was interested in science and medicine, came across B.E.S.T., and the rest is history. That was my first exposure to healthcare and medicine and I immediately recognized that I really enjoyed it, really loved learning about it. I wanted to keep pursuing it.”

Reese recently graduated from the University of South Florida and in addition to working with B.E.S.T., is working as an EMT in the Tampa Bay area. He plans to apply to medical school at the end of his gap year.

“Not so long ago, I was helping sixth-graders out with dissections — dogs, frogs, rats, fish, and sharks — and relating it back to human anatomy, explaining how organs worked and all of that. One of the students turned to me and said ‘You look like the older version of that kid over there.’

“It may seem like such a small moment but to me, [but] that’s the reason why B.E.S.T. even exists — to show students that there are people who look just like them achieving the things that they want to achieve one day.”

“At the End of the Day, It’s All About the Students”

After 17 years, over 15,000 students have graduated from the B.E.S.T. program. Many, like Diaz and Reese, are well on their way to pursuing medical careers or thriving already as PAs, doctors, nurses, and other healthcare personnel.

“There’s a sense of great satisfaction when it comes to being the founder of this organization,” Frederick says. “More importantly, I feel that the people who came alongside me, who trusted me and my vision, are the ones who should be applauded. Sure, I came up with this idea, but without their support, it would not have happened. It’s great to head the organization but at the end of the day, it’s about the students.”

For young people of color considering entering the medical field, Frederick says it’s a great time to go into healthcare. “When you have a community that is becoming very diverse, there needs to be an equally diverse population of clinical personnel to tend to that group. Minorities are underrepresented and receive better healthcare from people who look like them.”

For healthcare professionals interested in how they might help change the narrative of who works in medicine and further B.E.S.T.’s mission, Reese offers this advice: “Find ways to serve your community. It doesn’t matter what level you’re at professionally. Always be open to helping your community. Be vocal about your career and successes so that young people know those opportunities are out there.”

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn

Source: Read Full Article