Hokkaido University scientists are getting closer to understanding how a rare hereditary disease impairs the skin’s barrier function, which determines how well the skin is protected.

The gene mutation that causes ichthyosis prematurity syndrome—characterized by premature birth; difficulty breathing shortly after birth; and very dry, thick and scaly skin—dramatically reduces the synthesis of acylceramide, a key skin lipid in forming the skin barrier. The discovery provides us with a better understanding of the condition, which is currently untreatable.

Ichthyosis prematurity syndrome is caused by a gene mutation in fatty acid transporter member 4 (FATP4), but the details of how the mutation impairs the skin’s barrier function, leading to dry, scaly skin, has been unclear.

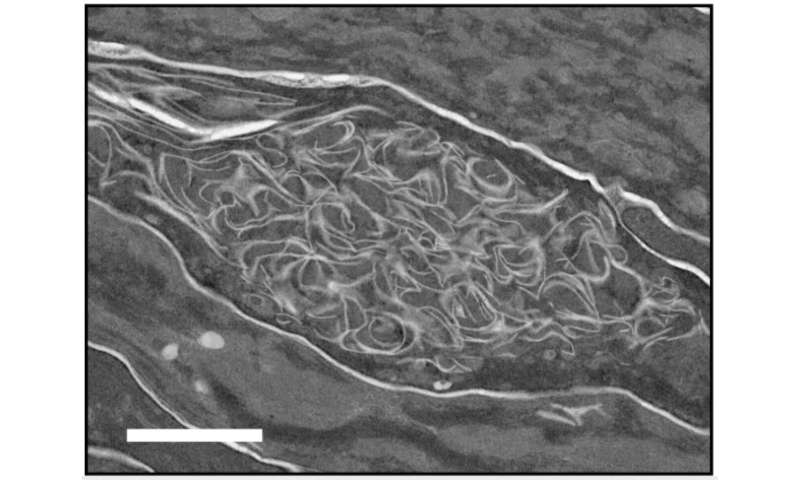

Molecular biologist Akio Kihara of Hokkaido University led a team of researchers in Japan and Germany to investigate the molecular mechanisms behind the disease. When they disrupted the FATP4 gene in mice, the offspring had rigid skin, low body weight, and died within an hour of birth. Water loss from their skin was more than four times higher than normal mice, and their skin was delicate, susceptible to staining.

Investigations revealed microscopic changes in the skin similar to those that occur in people born with ichthyosis prematurity syndrome. These included abnormalities in the outermost layer of the epidermis.

Upon further analysis, the researchers found a group of skin lipids called acylceramides were significantly reduced in the mice, having only 10 percent of the normal amount. Acylceramide plays a pivotal role in making the skin barrier largely impermeable to pathogens, allergens and chemicals. It also prevents water loss from the body.

Similarly, when the FATP4 gene expression was decreased in human keratin-producing skin cells, they showed a 40 percent reduction in acylceramide levels compared to normal human keratinocytes.

Source: Read Full Article