(Reuters Health) – The COVID-19 pandemic has hit Latinx communities especially hard, amplifying preexisting inequities and creating new disparities in health, income and social well-being, a new study suggests.

Based on interviews with 60 Latinx adults who survived a COVID-19 hospitalization in public hospitals in San Francisco and Denver, researchers found that five themes emerged: there was a misperception of COVID-19 as a distant and secondary threat; exacerbation of pre-existing disadvantage; a reluctance to seek medical care due to worries about cost and fears of deportation; fear of how the virus will affect healthcare system interactions; and belief that faith would protect against the virus.

“First, there is a need to provide care and to create policy solutions in a way that is concordant with Latinx culture and language,” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Lilia Cervantes, an associate professor in in the Department of Medicine at Denver Health Medical Center, in Colorado. “Second, because COVID-19 has been a compounder of pre-existing disadvantages, we need to treat immigrants as integral to any public health response. It’s the one community that consistently lacks safeguards around the country.”

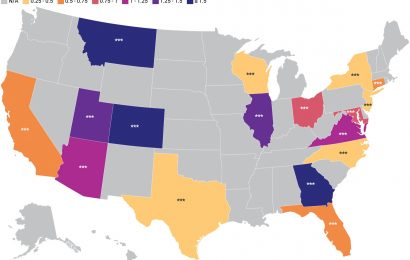

To learn more about the impact of COVID-19 on the Latinx community, Dr. Cervantes and her colleagues conducted semi structured interviews by phone with 60 Latinx adults who had been hospitalized for COVID-19 in two cities that have reported excess COVID-19 cases among Latinx individuals compared with the general population (54% versus 32% in Denver, and 51% versus 15% in San Francisco).

Among the participants, 24 were women, 36 were men, and the mean age was 48. All lived in low-income areas, 47 participants (78%) had more than four people in the home, and 44 participants (73%) were essential workers. Four participants (9%) could work from home, 12 (20%) had paid sick leave, and 21 (35%) lost their job because of COVID-19, according to the results published in JAMA Network Open.

An important theme arising from the interviews was people’s beliefs that COVID-19 wasn’t something to worry about. Some said that until they became ill, they thought the illness “was a bunch of lies,” while others said they “thought the government invented COVID-19.”

Fear of big doctor bills and of the possibility of being deported kept some from seeking care until they were very sick: “I kept telling myself to stay home, to bear the breathlessness, but once I couldn’t breathe anymore there was no other options,” one participant said. “We are fearful because we think (doctors and hospital staff) will share our information and immigration officials will take you, incarcerate you and deport you,” said another.

Others feared being isolated from their loved ones if they went to the hospital: “I was scared of going to the hospital because once you are there you can’t have any visitors. You are alone and if something happens to you, your family can’t come visit you. I was very scared I would die there.”

Some patients talked about how difficult it was to protect themselves from the virus when they could not work from home and needed to take public transportation.

Some of the solutions need to be enacted by government groups, Dr. Cervantes said. For example, immigrants generally end up with lower-wage jobs, she said. Because of that, they end up with multiple generations crammed together in small apartments or houses. “They have no choice but to live together to make ends meet and are thus at risk of exposing one another,” she added.

One solution is to offer respite for those with a positive COVID-19 test, Dr. Cervantes said. “Some states have been able to work with motels, hotels or other buildings for people with COVID-19 to live in while quarantining, she added.

“I really like this article and think it’s a very important contribution,” said Dr. Lynne Richardson, a professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and co-director of the Mount Sinai Institute for Health Equity Research in New York City. “We’ve all been watching the data on the disparate impacts of COVID-19 on the Black and Latinx communities. But hearing the experiences of individuals who were hospitalized talk about it in their own voices adds another dimension.”

It’s especially striking, Dr. Richardson said, to see how these voices confirm what the data have been showing: “people who can’t work from home, have to live together in large numbers and have to take public transportation are at increased risk. And those with poor access to healthcare prior to the pandemic are likely to have worse outcomes when they do contract the virus.”

The article also spotlights “the pervasive fear of unemployment, eviction and deportation and how that interfered with their seeking care when they needed it,” Dr. Richardson said. It also underscores the importance of getting the facts out to the Latinx community from “trusted messengers,” she added.

The study gives “a granularity that you can’t get from big data,” said Dr. Kathleen Page, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, in Baltimore. “This is very similar to what we have seen here in Baltimore. It’s been very difficult for Latinx (immigrants), many of whom have low English proficiency, low income and are without a doctor.”

Dr. Patricia Documet applauded the authors for interviewing a large number of people from two medical centers. “It’s a lot of people who were in intensive care so it can provide a clear picture of what they went through,” said Dr. Documet, a professor of behavioral and community health science and director of Latinx Research and Outreach at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

The article also underscores the big role misinformation has played, Dr. Documet said. “Most are getting information from social media, mostly Facebook, and that’s problematic,” she added. “People were dismissing COVID. They didn’t think it was important. And then after hospitalization they now know it exists. And they feel responsible for telling people that it is real.”

SOURCE: https://bit.ly/38z5CLS and https://bit.ly/3rCWVYl JAMA Network Open, online March 11, 2021.

Source: Read Full Article