Humans are exposed to many types of bacteria daily, the majority of which are harmless. However, some bacteria are pathogenic, which means they can cause disease. An extremely common pathogenic bacterial infection is Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in the stomach, where it can lead to chronic inflammation (gastritis), ulcers, and even cancer. A group of researchers from Osaka University have determined a specific molecular mechanism that H. pylori uses to adapt to growing in the human stomach for long periods of time.

In a report published in Nature Communications, this group found that a small RNA molecule called HPnc4160 plays a key role in how H. pylori invades the stomach and leads to disease.

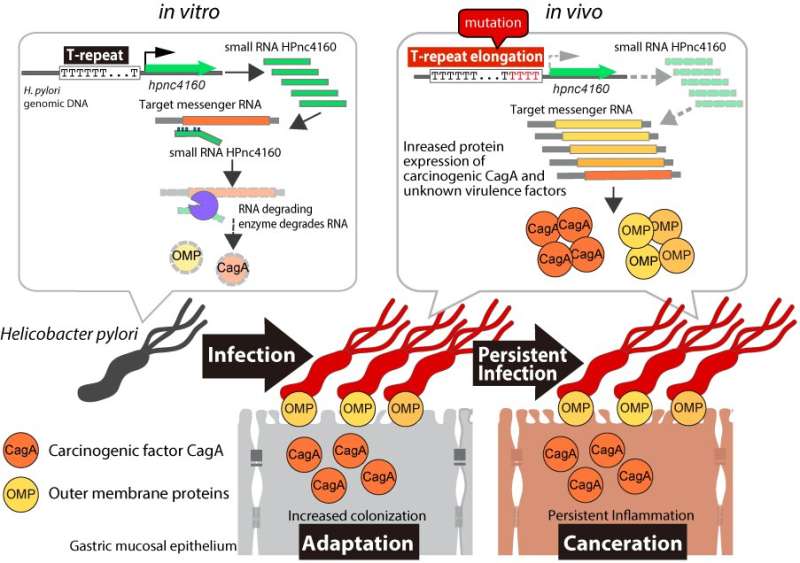

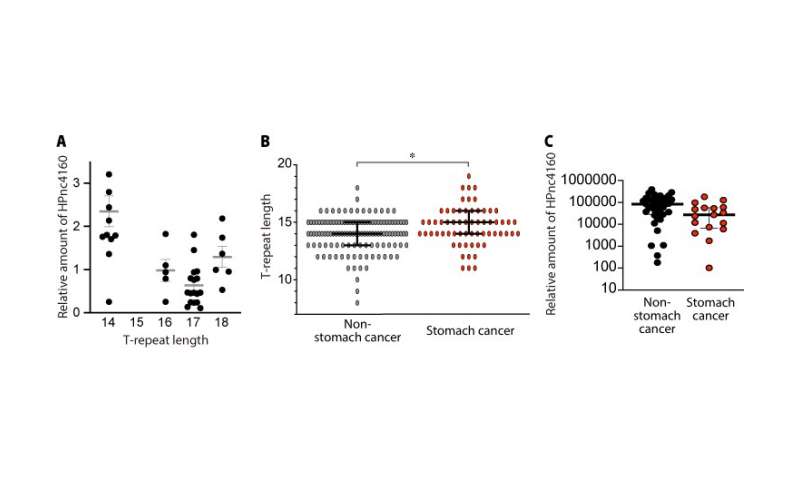

Previous studies showed that HPnc4160 is conserved in different strains of H. pylori, suggesting that it has an important function. Yet, the amount of this molecule produced in the bacteria is variable among strains. Genetic analysis revealed that a specific part of the H. pylori gene, called the T-repeat region, varied in length from strain to strain. The researchers became interested in how this region affected HPnc4160 expression. Additionally, they were curious how these fluctuations would allow some strains to colonize the human stomach more efficiently than others.

“Slight differences in the genetic sequence of H. pylori can sometimes give certain strains advantages over others that allow it to grow better,” says lead author of the study Ryo Kinoshita-Daitoku. “We were interested in the genetic and molecular reasons behind why particular strains are more pathogenic and can live in the stomach for decades, leading to cancer development.”

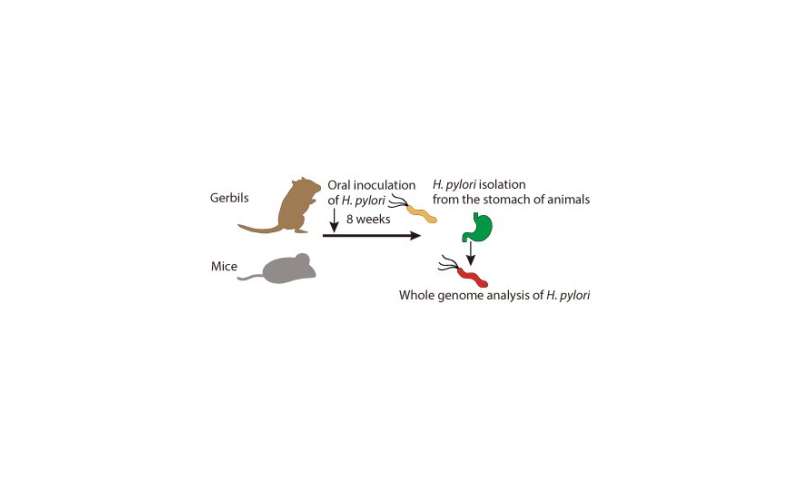

To address these questions, the researchers infected gerbils and mice with wild type (normal) H. pylori for 8 weeks, then extracted and genetically characterized the mutant strains that appeared. They discovered that strains with a higher number of T-repeats had lower expression of HPnc4160.

“We found that the H. pylori strains with low HPnc4160 levels were more infectious,” explains Hitomi Mimuro, senior author. “When this RNA was completely absent, the amounts of several bacterial pathogenic factors significantly increased and the strain showed stronger colonization within the rodent stomach.”

One of the pathogenic factors was the bacterial protein CagA, which is known as an oncoprotein because it can promote cancer development.

“Interestingly, we observed longer T-repeat regions, lower levels of HPnc4160, and higher levels of CagA in gastric cancer patients compared with those not suffering from cancer,” describes Kinoshita-Daitoku.

Source: Read Full Article