News that France had fallen further behind in the race to develop COVID-19 vaccines caused dismay on Tuesday, reigniting a debate about the country’s standing in the world and its scientific prowess.

France has a celebrated history of medical breakthroughs, including from Louis Pasteur, a pioneer in microbiology and the inventor of vaccines against rabies and anthrax.

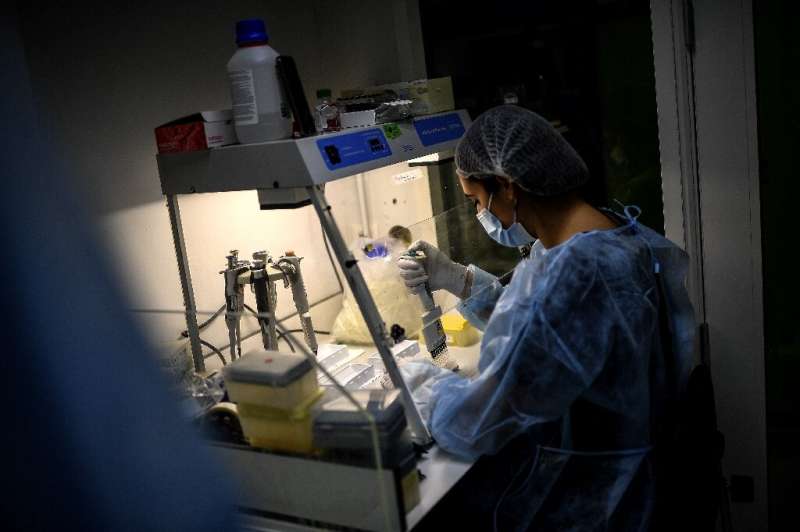

With the world-renowned research centre that bears his name in Paris, the Pasteur Institute, as well as leading pharma group Sanofi, the country looked well placed to produce its own jab to protect against coronavirus.

But the Pasteur Institute announced Monday that it was abandoning research on its most promising prospect, while Sanofi has said its candidate for inoculation will not be ready before the end of 2021 at best.

“It’s a sign of the decline of the country and this decline is unacceptable,” Francois Bayrou, a close political ally of pro-business President Emmanuel Macron, said Tuesday.

Bayrou, head of the centrist MoDem party and named by Macron last year as commissioner for long-term government planning, said the problem was a brain-drain from France to the United States.

Speaking on France Inter radio, he said it was “not acceptable that our best researchers, the most brilliant of our researchers, are sucked up by the American system”.

He referred to Stephane Bancel, a Frenchman who heads US-based biotech firm Moderna, whose vaccine was the second to be approved for use in the United States and Europe.

Experts say the US government has invested more in vaccine research in the previous decades, while innovative companies are also drawn to the country because raising funds from private investors is easier and quicker.

Long-time Socialist minister and ex-presidential candidate Segolene Royal blamed “liberal ideology” for reductions in public funding for vaccine research, while Communist Party head Fabien Roussel called the setbacks a “humiliation”.

Nostalgia and rivalry

The failure of French COVID vaccine research so far touches on several sensitive issues for the country.

The political class and many voters have long worried about France’s relative decline in power and influence—the ominous “declassement”—in an increasingly globalised world.

This tendency is seen by many analysts as part of the explanation for strong support for the far-right party of Marine Le Pen, whose rhetoric is tinged with nostalgia for the supposed glory days of the last century.

Since World War II, French governments have always had a strong industrial policy which has seen the promotion and protection of national champions amid particular rivalry with “les anglo-saxons” in Britain and America.

Sanofi, the only remaining major French pharma group, has come in for fierce public criticism, particularly in May last year when CEO Paul Hudson—a British citizen—said the United States would get any vaccine it produced before the rest of the world.

The group followed up this public relations disaster at home by announcing 1,700 job cuts a month later, including 1,000 in France.

Amid the self-criticism and introspection, some experts and politicians have called on France to avoid taking the vaccine setbacks too hard.

Chance plays a major role in cutting-edge research, evident in the work of the most celebrated past French researchers from Pasteur to Nobel Prize-winning chemist Marie Curie.

Nathalie Coutinet, an economics of medicine researcher at the Sorbonne University in Paris, said many different approaches were being taken by scientists worldwide in the COVID fight.

The Pasteur Institute bet on adapting a measles vaccine to fight COVID, while Sanofi tried to tweak one of its flu jabs.

The most successful approach among Western researchers turned out to be “messenger RNA,” which was harnessed by German biotech group BioNTech as well as Moderna, whose jabs have been approved.

Source: Read Full Article