Researchers led by University of Toronto psychologist Willis Klein have investigated an understudied form of relationship abuse—gaslighting. In a paper titled “A qualitative analysis of gaslighting in romantic relationships,” published in the journal Personal Relationships, the study looks into the signs of coercive control and the effects of gaslighting, a form of intimate partner violence (IPV), on survivors.

Survivors of gaslighting (n=65) were invited to a survey with 15 open-ended questions about their experiences, the trajectory of the abusive relationship, specific instances of gaslighting, personal consequences resulting from their relationship, how the relationship affected their self-concept and the degree to which they had recovered from the abuse.

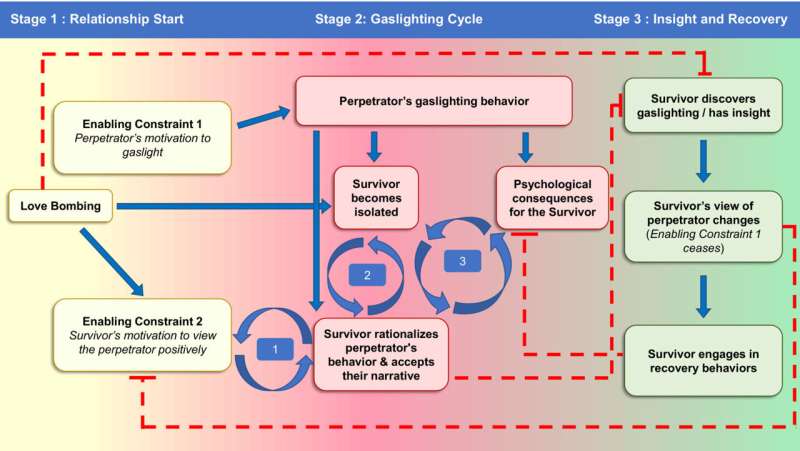

Specifically, the study wanted to examine if gaslighters gained more social power than their survivors, determine if gaslighters typically had an objective goal or used the tactic for a more widespread set of motivations, provide empirical evidence to compare with gaslighting tactics outlined in self-help literature, investigate whether there are specific stages of gaslighting relationships (including the presence of love-bombing) and determine whether ending the relationship facilitates recovery.

Love-bombing, a form of excessive romantic communication, was found in most responses, typically at the beginning of the relationship. It can be in the form of gifts, frequent compliments and heightened levels of attention that can be overwhelming and monopolize the time of the subject, isolating them from others. As the name implies, it can also include the love bomber saying “I love you” often and in the very early stages of a relationship.

The findings indicate that the motivation for gaslighting appears related to coercive control tactics. Gaslighters who were motivated by a desire to control their partners engaged in a wider variety of coercive control tactics, including setting rules, verbal abuse, property damage and threats. Accusations of incompetence, characteristic of gaslighting, and attempts to isolate the survivor were common.

Isolation was seen as an integral part of the controlling behavior, often beginning with negative opinions about members of survivors’ friends and family. Isolating the survivor kept them from receiving advice about their partner’s questionable behaviors, made the survivor more reliant on the gaslighter for social attention and may have contributed to survivors’ sense of “losing their grip” on reality.

Survivors reported frequent accusations of cognitive incompetence, mental instability or being “overly emotional,” sometimes in the form of concern for survivors but more often framed as insults. Tactically, these directly challenge the survivors’ self-knowledge and diminish their sense of reality.

Perpetrators also attempted to exert control by limiting survivors’ ability to accomplish goals external to the relationship, such as pursuing school or career advancement, through constantly undermining self-confidence and self-esteem.

Survivors of gaslighting relationships reported a diminished sense of self, increased guardedness, and increased mistrust of others long after the relationship ended. Some participants reported that they had not recovered from their gaslighting relationships.

Recovery post-gaslighting

Despite reports of increased mistrust, socializing was the activity most reported in response to questions about recovery. Engaging or re-engaging with others in activities helped many survivors regain a sense of self. Creative hobbies with a strong self-expression component, like art or writing, also allowed the return of self-knowledge and self-identity.

Finally, the study indicates that gaslighting is a traumatic experience, and post-traumatic personal growth can be positive. Survivor recovery narratives usually focused on establishing healthier relationship boundaries or having a “clearer” and “stronger” sense of self.

More information:

Willis Klein et al, A qualitative analysis of gaslighting in romantic relationships, Personal Relationships (2023). DOI: 10.1111/pere.12510

© 2023 Science X Network

Source: Read Full Article