Getting everyone who is eligible for free or discounted health insurance to sign up for it requires making it as easy as possible to enroll—and that convenience especially matters for young, healthy and low-income people. Those are the key findings of a recent study I conducted with Myles Wagner, an economics Ph.D. student.

We examined the subsidized health insurance program for low-income Massachusetts residents enacted in 2006 when Mitt Romney served as the state’s governor. The Massachusetts program—dubbed RomneyCare—resembled the program created by the Affordable Care Act and served as its model. For residents below the poverty line, which then stood at about US$22,000 for a family of four, coverage cost nothing.

Even when they didn’t have to pay a dime, eligible residents still had to sign up using a two-step process: After applying, they chose a plan among four or five options.

But the program didn’t always work this way. The state government didn’t make beneficiaries choose a plan until 2010. Instead, anyone who qualified but didn’t respond when asked to select one was automatically enrolled in a plan the state picked out. This meant that no one would go without insurance if they forgot to respond or got confused by the rules.

We compared the number and socioeconomic characteristics of residents who enrolled in the program before and after the change, with a control group unaffected by the policy because they had higher incomes and were not eligible for auto-enrollment.

We found that having a streamlined process makes a big difference. With automatic enrollment, 48% more people signed up for coverage each month. This meant one-third more people obtained coverage over the long run, and it reduced the uninsured rate among low-income people eligible for this coverage by about 25%.

A one-step process also had other consequences. Those who were automatically enrolled were especially likely to be young and healthy, with health care costs 44% below average.

They were also more likely to reside in low-income neighborhoods.

Massachusetts ended auto-enrollment in 2010 for budgetary reasons, and it didn’t reinstate it when the state shifted to an Affordable Care Act market in 2014.

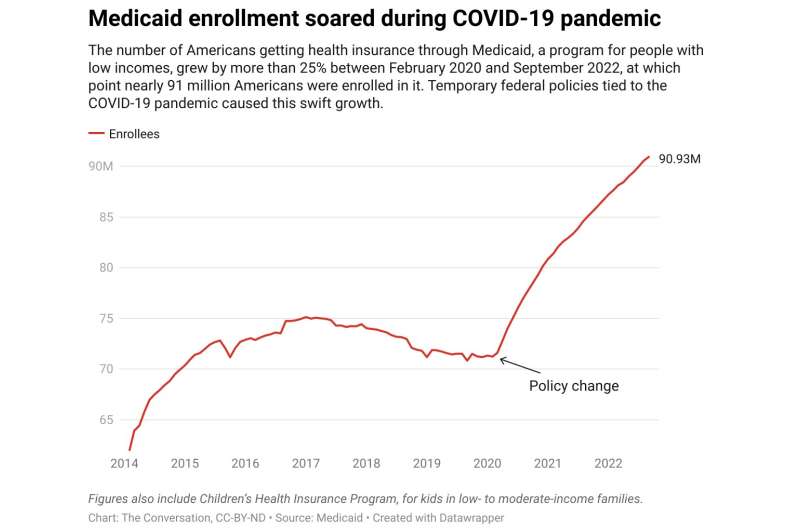

About 5 million to 14 million Americans could soon lose their health insurance coverage through Medicaid—the government-funded U.S. health insurer for low-income Americans.

That’s because once the federal government designated the COVID-19 pandemic a “public health emergency” in March 2020, it changed Medicaid rules.

In exchange for agreeing to not remove anyone from the program, the states got more funding to run it.

The number of people enrolled soared to 90.9 million in September 2022, up 28% from February 2020. That’s roughly 1 in 4 of all Americans.

But the government’s continuous enrollment policy is slated to expire starting in April and the public health emergency is scheduled to officially end on May 11, 2023.

Unless those whose coverage expires actively sign up for new coverage, they could become uninsured—even if, like many uninsured Americans today, they would qualify for free or discounted coverage if they were to apply through an ACA health insurance exchange.

It’s still unclear how automatic enrollment policies can comply with the ACA’s rules to limit the number of people who will otherwise become uninsured when they lose Medicaid coverage.

But there are a variety of different proposals out there. Some states, including Maryland, California and—no surprise—Massachusetts, are starting to experiment with different approaches.

So once the pandemic-related Medicaid policies end, there will probably be new evidence that suggests which design works best.

Provided by

The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: Read Full Article