To better understand the causes of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), it is crucial to look at what is happening in the brain during development. The closest we come to observing human brains this early is by using organoids—miniature models of organs. With their help, scientists at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) discovered how mutations in a high-risk gene of autism disrupt important developmental processes.

Several hundred genes are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Some patients are only mildly affected, while others have severe disabilities. In addition to characteristic symptoms like difficulties in social interaction and communication with other people, as well as repetitive-stereotypic behaviors, patients with mutations of the gene CHD8 oftentimes have intellectual disabilities and macrocephaly—an unusually large brain. How CHD8 causes these symptoms has long been unclear.

Tiny artificial brains

Since CHD8 mutations affect the brain at a very early stage of its development, it has proven difficult for scientists to get the full picture. Over the past years, many researchers therefore used mice as model organisms to better understand what is going on. “But mice with a CHD8 mutation barely showed the symptoms human patients are showing. The effects in mice are not comparable to humans. We needed some kind of human model,” Professor Gaia Novarino explains.

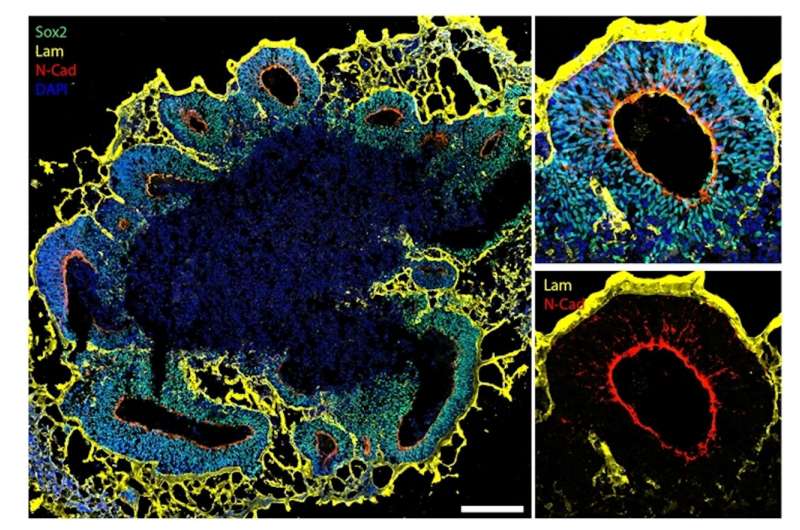

Together with collaborators from the Italian Human Technopole institute, the European Institute of Oncology, and the University of Milan, as well as the Allen Institute for Brain Science, U.S., Novarino and her team at ISTA turned to organoids. These simplified miniature versions of organs are made from stem cells, which have the ability to become almost every other type of cell. By creating the right circumstances and giving the proper input at just the right time, the scientists were able to mimic developmental processes to create basic versions of brain tissue the size of lentils. “Organoids are the only way you can study human brain development at such an early phase,” says Bárbara Oliveira, postdoc in the Novarino group and one of the authors of the study.

CHD8 mutations disrupt balance of neuron production

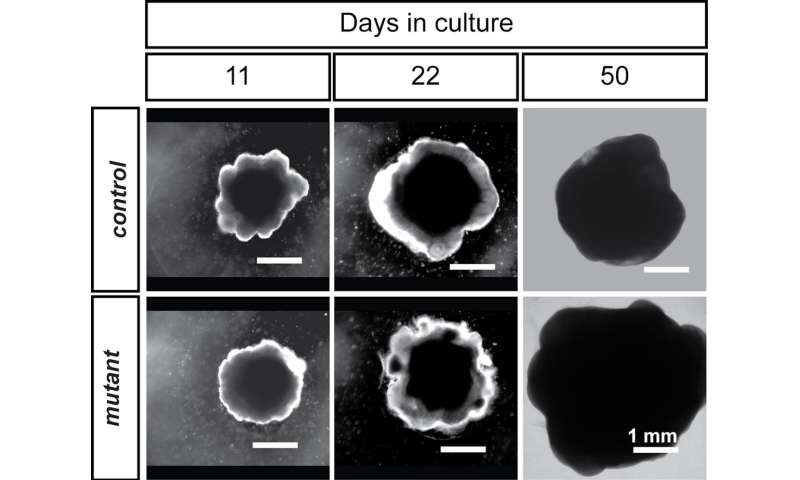

In petri dishes the team created brain organoids with and without mutations of the gene CHD8. “After some time, we could see by eye that the mutant organoids were much bigger. That was the first evidence that the model works,” her colleague and co-author, Ph.D. student Christoph Dotter, describes. Like patients with a CHD8 mutation, the organoids were showing signs of brain overgrowth.

Getting an overview of all the cell types in the organoids, the team notices something very early on: The mutant organoids started to produce a specific type of neurons, inhibitory neurons, much earlier than the control group. So called excitatory neurons, however, were produced later. Furthermore, the mutant organoids produced much more proliferating cells that later on produce a larger amount of this kind of neurons. Over all, the scientists concluded, this leads to them being significantly bigger than the organoids without CHD8 mutations correlating with patient’s macrocephaly.

Starting to understand our brain

Source: Read Full Article