A fundamental discovery about a driver of healthy development in embryos could rewrite our understanding of what can be inherited from our parents and how their life experiences may shape us.

The new research suggests that epigenetic information, which sits on top of DNA and is normally reset between generations, is more frequently carried from mother to offspring than previously thought.

The study, led by researchers from WEHI (Melbourne, Australia), significantly broadens our understanding of which genes have epigenetic information passed from mother to child and which proteins are important for controlling this unusual process.

At a glance

- First study to find a protein in the mother’s egg that regulates the epigenetic inheritance of a set of genes critical for the development of normal body structure in mammals.

- While the epigenome can be influenced by the environment, including someone’s diet and exposure to pollutants, these epigenetic changes are very rarely inherited.

- Discovery transforms our understanding of what can be passed down, indicating epigenetic inheritance may occur more frequently than previously thought.

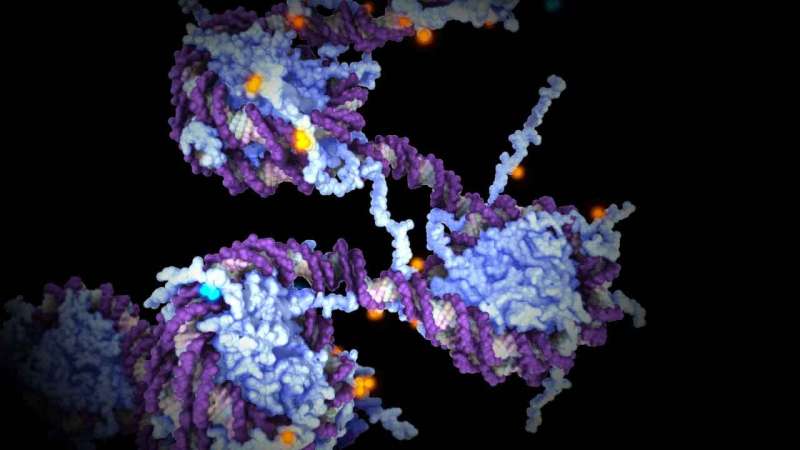

Epigenetics is a rapidly growing field of science that investigates how our genes are switched on and off to allow one set of genetic instructions to create hundreds of different cell types in our body.

Epigenetic changes can be influenced by environmental variations such as our diet, but these changes do not alter DNA and are normally not passed from parent to offspring.

While a tiny group of “imprinted” genes can carry epigenetic information across generations, until now, very few other genes have been shown to be influenced by the mother’s epigenetic state.

The new research reveals that the supply of a specific protein in the mother’s egg can affect the genes that drive skeletal patterning of offspring.

Chief investigator Professor Marnie Blewitt said the findings initially left the team surprised.

“It took us a while to process because our discovery was unexpected,” Professor Blewitt, Joint Head of the Epigenetics and Development Division at WEHI, said.

“Knowing that epigenetic information from the mother can have effects with life-long consequences for body patterning is exciting, as it suggests this is happening far more than we ever thought.

“It could open a Pandora’s box as to what other epigenetic information is being inherited.”

The study, led by WEHI in collaboration with Associate Professor Edwina McGlinn from Monash University and The Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute, is published in Nature Communications.

Astonishing discovery

The new research focused on the protein SMCHD1, an epigenetic regulator discovered by Professor Blewitt in 2008, and Hox genes, which are critical for normal skeletal development.

Hox genes control the identity of each vertebra during embryonic development in mammals, while the epigenetic regulator prevents these genes from being activated too soon.

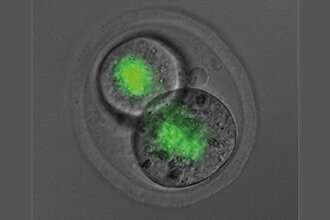

In this study, the researchers discovered that the amount of SMCHD1 in the mother’s egg affects the activity of Hox genes and influences the patterning of the embryo. Without maternal SMCHD1 in the egg, offspring were born with altered skeletal structures.

First author and Ph.D. researcher Natalia Benetti said this was clear evidence that epigenetic information had been inherited from the mother, rather than just blueprint genetic information.

“While we have more than 20,000 genes in our genome, only that rare subset of about 150 imprinted genes and very few others have been shown to carry epigenetic information from one generation to another,” Benetti said.

“Knowing this is also happening to a set of essential genes that have been evolutionarily conserved from flies through to humans is fascinating.”

The research showed that SMCHD1 in the egg, which only persists for two days after conception, has a life-long impact.

Variants in SMCHD1 are linked to developmental disorder Bosma arhinia microphthalmia syndrome (BAMS) and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD), a form of muscular dystrophy. The researchers say their findings could have implications for women with SMCHD1 variants and their children in the future.

Source: Read Full Article