Couples with higher relationship satisfactions showed greater linkage in their physiological responses (for example, heart rate and skin conductance) during face-to-face interactions, which suggests a greater “biological connection” between the couples.

This is according to a variety of studies, including a recently published paper in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology by Dr. Robert Levenson and Dr. Kuan-Hua Chen at the University of California, Berkeley.

In addition, there has been emerging evidence further suggesting that “being physically linked” with a partner’s physiological response may even have important implications to individuals’ mental and physical health.

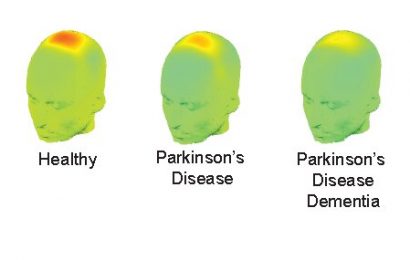

For example, findings from Levenson and Chen’s group suggested that a couple’s physiological linkage can predict their mental and physical health – in both healthy married couples and couples in which one person is the spousal caregiver of the other who is diagnosed with a neurodegenerative disease.

“In the past, our tools were limited to consumer wearable watches, which are typically expensive, need to be charged frequently, have restricted rules of data access, and do not provide accurate location data that are necessary for us to give a meaningful interpretation of the observed behaviors.”

Dr. Robert Levenson, University of California, Berkeley

Building upon this, researchers wanted to better understand whether synchronicity of objective physiology indicators between dementia patients and their caregivers also correlates to the influences between each other outside the laboratory, in real life.

In one recent study, Levenson and Chen had 22 patients, and their spousal caregivers wear a wrist-mounted actigraphy-monitor in their homes for seven days. They found that the more “linked” (particularly more synchronized) the patient’s and the caregiver’s activity was, the less anxiety the caregiver reported.

THE PROBLEM

In all of the above studies, the linkage and relationship/health data were collected around the same time, and therefore the researchers could not know whether greater linkage produced better relationship/health outcome, or vice versa, or both at the same time.

In addition, research participants in these previous studies were mostly living in the San Francisco/Northern California areas. Therefore the researchers could not know whether the effects that they found could be generalized to couples living in other, more rural areas in the United States.

PROPOSAL

To address these issues, Levenson and Chen launched a research project that recruited 300 patients and their familial caregivers (with the total number of participants at 600) to study their activity linkage in their homes for six months.

Over the study period, both the patients and caregivers wear the Tracmo CareActive Watch continuously for those six months, and caregivers are monitored periodically for mental and physical health changes.

“Researchers are eager to conduct studies in the field – for example, in people’s homes – and collect real-world behavioral data in complement to laboratory studies,” said Levenson, director and principal investigator at the University of California, Berkeley.

In the past, our tools were limited to consumer wearable watches, which are typically expensive, need to be charged frequently, have restricted rules of data access, and do not provide accurate location data that are necessary for us to give a meaningful interpretation of the observed behaviors.”

Compared with consumer wearable watches, the Tracmo CareActive solution is more affordable and overcomes the battery-life limitation, he added. It provides accurate room-to-room location information for research participants, and allows the team to access high-quality actigraphy data sampled with high temporal resolution (that is, in seconds), he explained.

MEETING THE CHALLENGE

The Berkeley research team provided two CareActive watches and three stations to each household, which included one participant with dementia or mild cognitive impairment and one familial caregiver. Participants install these devices at home through a CareActive App.

“The CareActive watch can be worn for more than three months without battery replacement,” said Chen, post-doctoral research fellow at the University of California, Berkeley. “Our study is extremely benefited by CareActive watch’s long battery life, because any single battery charging could interrupt our data collection.”

“The room-to-room locations are important for us to better understand and interpret our participants’ daily behaviors.”

Dr. Kuan-Hua Chen, University of California, Berkeley

More important, remembering to charge the watch routinely and put the watch back on after charging could be stressful and burdensome for research participants, particularly for those who are older and/or with age-related neurological conditions, he added.

“Besides, unlike typical consumer watches that use GPS to localize the users, [and] therefore can only provide approximate user locations on a map, the CareActive system uses Bluetooth signal strength that allows precise room-to-room mapping of our research participants when they are in their homes,” he said.

“The room-to-room locations are important for us to better understand and interpret our participants’ daily behaviors, including behaviors occurring at both the individual level. For example, a person may stay in the bedroom when he feels sick, or the dyadic level, … couples who feel happier with their relationships may spend more time being in the same room.”

RESULTS

In the ongoing research project that started in mid-March 2020, the Berkeley team has successfully collected CareActive data from more than 90 homes, distributed across 33 states in the U.S. All participants self-installed the systems with minimal assistance from the research team.

ADVICE FOR OTHERS

“All technology designed to be used in healthcare needs to consider the user’s backgrounds and needs,” Levenson advised. “When we study people with dementia and their familial caregivers, we put essential effort to simplify the steps for device installation, minimize the amount of work for maintenance, and maximize research participants’ motivation and benefit from using the device.”

Social-contextual factors and individual differences need to be considered when interpreting any information collected from the users, he added.

“For example, a fall-like behavior occurring in the bedroom may have different meanings than [one] occurring in the bathroom,” he said. “In addition, all homes have different sizes and layouts, [so] therefore we should be careful when generalizing patterns learned from one home to another.”

The Berkeley team would recommend, if possible, collecting additional information from other sources to cross-validate and improve interpretation/prediction accuracy – for example, integrating motion sensor data with Bluetooth proximity – he concluded.

Twitter: @SiwickiHealthIT

Email the writer: [email protected]

Healthcare IT News is a HIMSS Media publication.

Source: Read Full Article