A small proportion of women who receive anti-estrogen treatment after breast cancer surgery have worse outcomes. This is associated with mutations in the estrogen receptor gene, according to a study from Lund University now published in JNCI Cancer Spectrum.

“If our results are confirmed in further studies, it would be relevant to screen for these resistance mutations already at diagnosis, and then consider other treatment options that could work better for patients with mutated tumors,” says Lao Saal, who led the study, the largest of its kind on resistance mutations in the estrogen receptor in primary breast cancer.

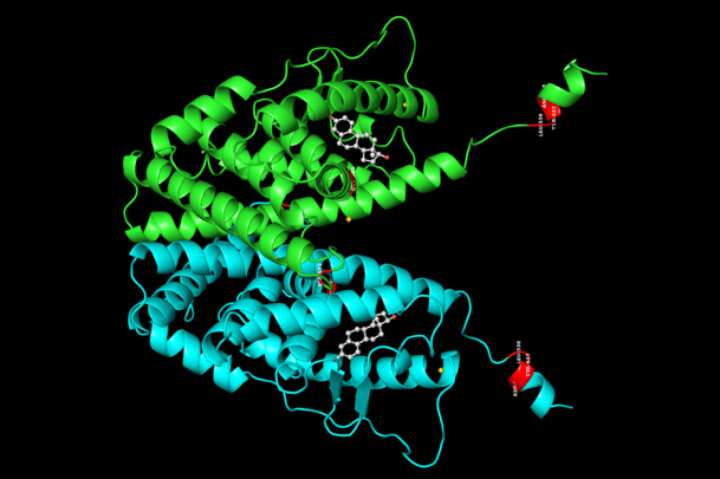

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer in women. The majority of breast tumors have high levels of the estrogen receptor (encoded by the gene ESR1), and after surgical removal of the cancer, the most important treatment for these women are anti-hormonal drugs that reduce the activity of the estrogen receptor and thereby reduce the risk of relapse.

The researchers focused on the mutations in the estrogen receptor ESR1 gene, which had been previously discovered to be common in relapsed breast cancer in women who had received prior anti-estrogen cancer treatment. The mutations made the tumor resistant to the hormonal treatment. Recent studies, however, showed that the incidence of these resistance mutations was very low in patients at the first diagnosis of cancer, and no studies explored how such pre-existing mutations might be related to response to anti-hormonal treatments.

The Lund researchers analyzed RNA-sequencing data from more than 3,000 breast tumors from within the large SCAN-B research project, samples taken before treatment with drugs. Among the 2,720 tumors positive for the estrogen receptor and therefore eligible for hormonal treatment, they found 29 tumors with an ESR1 resistance mutation. All mutations were found in patients older than 50 years.

“We investigated whether the resistance mutations, which occurred before cancer treatment, affected the patients’ survival and saw that patients with a mutation in their primary tumor had three times higher risk of recurrence and 2.5 times higher risk of dying. The link between the mutations and poor survival was also seen after statistical corrections for age or for other factors that may affect the outcome for the patient,” says doctoral student Malin Dahlgren.

Source: Read Full Article