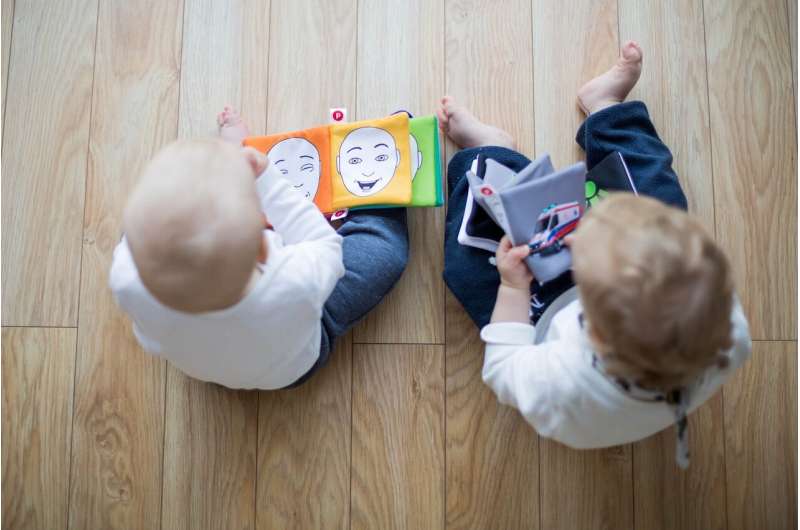

Toddlers and preschoolers in family child care homes ate healthier and were more physically active if the provider was coached in best practices and shown ways to meet those expectations, according to the findings of a new study from UConn and Brown University researchers.

The study, Healthy Start/Comienzos Sanos, looked at 400 children ages two to five in 120 family child care homes within a 60-mile radius of Providence to gauge over eight months whether certain interventions would influence the quality of foods being served and change the frequency of sedentary activities. The results were published in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity.

“There’s lots of data that shows the earlier children are exposed to healthy foods and the earlier they get accustomed to eating those foods, the more likely they are to carry those habits into later childhood and into adulthood,” UConn human development and family sciences professor Kim M. Gans, one of the lead researchers, says.

“We looked at children in family child care homes because there is some national data that shows kids who are cared for in this setting may have a higher risk of obesity,” she adds.

Family child care homes are different than center-based day cares in that licensed providers look after only a handful of children at their residences, which gives young kids the feeling of being at home versus being in school. While some do have an educational curriculum, many have unstructured days but offer the benefit of more one-on-one attention.

Gans said that while most research focuses on center-based day care, there’s been little conducted on family child care homes, even though 26% of U.S. children who are in care while their parents work, or 2 million, are enrolled in such programs.

At the start of the study, researchers surveyed the homes and did in-person interviews with caregivers, before a two-day observation during which they recorded what was going on in the home, including foods served, what actually was eaten, and the type and duration of physical activity.

Then, over eight months, caregivers received monthly feedback on areas that could benefit from improvement based on the 26 best practices outlined with the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care, known as NAP SACC.

With this and from meetings with a peer coach, caregivers developed a goal for each month. They also received a monthly newsletter and video related to their goal and participated in support group meetings with others in the study.

Half the homes received interventions related to nutrition and physical activity, the other half had interventions that centered on reading readiness. Consequently, each home received either a box of toys to promote physical activity, such as hula hoops, soft balls, tunnels, and bean bags, or books and other materials related to reading readiness.

“We found that children in homes in the nutrition and physical activity group improved their diet quality more than the children in the homes that received the reading and literacy readiness intervention,” says Gans. “We also saw that those children reduced their sedentary time more than the children in the literacy group.”

Using a Healthy Eating Index score, researchers also found that the vegetable and added sugar scores changed for the better during the intervention period compared to the literacy group.

Further, “We put activity monitors on the children to record how active the kids were,” says Gans. “We saw a relationship between outside time and activity levels. The more outside time the provider gave the children, the more physically active they were. That made a difference.”

Details on whether the literacy group improved their reading readiness skills over the group that focused on nutrition and physical activity will be the subject of a future paper, she adds.

“The family child care providers were extremely interested in getting an intervention because they wanted to learn more,” Gans says. “We found that providers were very concerned about the health of the kids. They really feel like an extended family member, and they want more training to do a better job of providing healthy foods and activities for kids.”

During the observations, researchers noticed many homes didn’t offer self-serve water for the children or water breaks after outside activities, Gans says. “Not a lot of them were prompting children to drink water. They had water dispensers on their refrigerators and things like that, but they weren’t necessarily actively prompting children to drink water.”

Similar to the Healthy Start/Comienzos Sanos study, Gans says, Drink Well/Bebe Bien is a new study that will assess issues around water intake and access in family child care homes. Researchers now are seeking 40 family child care providers in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island to participate in the study that also will include surveys and intervention supplies, such as water testing, water filters, water bottles, and water pitchers.

“There is data showing hydration is not adequate in kids, especially younger kids, and people tend to overserve milk and juice and they don’t think about water,” Gans says. “It’s similar to food. If you get kids used to drinking water, they’ll keep drinking water. But if they’re used to drinking only sweetened juice, milk, or sugar-sweetened soda, that’s what they’re going to want to drink going forward.”

She stresses that this is a ubiquitous problem that’s not specific to family child care homes or even day care situations exclusively.

Source: Read Full Article