While some countries have tried to contain the new coronavirus with widespread testing, others have imposed lockdowns to save lives in the face of concerns over the economic hardships they will involve.

Still others are letting the virus circulate almost unimpeded, hoping to avoid health system collapse while perhaps edging towards “herd immunity”—despite fears that this might be out of reach.

Here are some of the different approaches to tackling the pandemic:

Lockdowns: the price of protection

Following in China’s footsteps, many countries have imposed strict confinement measures on their populations to try to slow the spread of the virus.

Facing rapidly mushrooming caseloads Italy, Spain, France and Britain were among the European countries to conclude that locking down citizens was the only option.

The restrictions are not for the most part aimed at ending the epidemic, but to prevent the hospital system from being overwhelmed by a tidal wave of patients needing acute respiratory support.

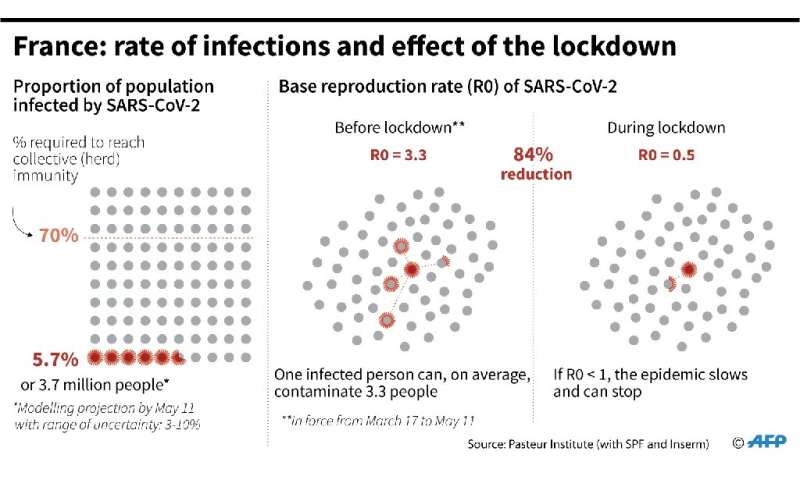

The aim is to reduce infections by limiting contact between individuals—to “flatten the curve” of infections.

And in this respect the lockdown measures have largely begun to succeed. Most experts agree that they have saved many thousands of lives.

But they have come with a steep cost, ushering in a global economic recession that is predicted to be savage.

There are also grave concerns about severe societal and health side effects, including growing inequality, domestic violence, mental health problems and worsening medical problems other than COVID-19.

Experts have warned these consequences could themselves lead to deaths.

In an article this month in the European Journal of Cancer, three specialists said critical prevention and treatment work was being sidelined in the push to tackle COVID-19.

“Denying that this downside exists will mean that we will be adding the lost lives of cancer patients to the COVID-19 death count toll,” they argued.

Public health measures can also become victims of their own success.

If restrictions sharply slow the virus, for example, people could become complacent and less likely to accept further curtailments to their freedom of movement.

Piecemeal lifting of lockdowns will need to be accompanied by widespread testing, contact tracing for those infected, and isolating those with COVID-19 to avoid igniting another fast-moving infection surge.

South Korean surveillance

After discovering its first cases, South Korea launched a widespread system to identify those infected, quarantine positive cases, trace all the people they had come into contact with and test them as well.

In doing so, the country has become the model for the World Health Organisation’s exhortation to: “Test, Test, Test”.

It is this strategy, also implemented by other authorities in parts of Asia, that many European countries emerging from containment aspire to implement.

But for this to work you need a huge “quantity of tests, quantity of masks, digital tools and enormous numbers of personnel” to help trace potential patients, said French epidemiologist Dominique Costagliola.

Furthermore, the strategy is not a long-term guarantee, particularly if it has blind spots.

Singapore, which had also used the test and trace strategy to get its epidemic under control, has seen an explosion of cases since it started testing migrant workers, many of whom live in tightly-packed dormitories.

The city-state on Wednesday announced that it would keep tightened restrictions in place until June after a surge in cases, mostly among migrants, took the country’s caseload above 9,000.

Herd immunity: a gamble?

While its neighbours have hunkered down under strict lockdowns, Sweden has continued to socialise—albeit in small groups.

The government has not imposed a lockdown on its population, rather it has appealed to people to act responsibly and apply social distancing.

The only restrictions imposed by the Scandinavian country of over 10 million people are the closure of high schools and colleges, bans on gatherings of more than 50 people and on visits to retirement homes.

Swedish epidemiologist Johan Giesecke has described the virus as a “tsunami”, but brushed aside concerns over its severity, estimating that half of the population in the country may already have had COVID-19.

He said that while “herd immunity”—the proportion of the population that has had the virus and developed antibodies—was not an aim of the policy, it was a by-product.

“The strategy is to protect the old and the frail,” he said in an interview with the website UnHerd.

But he added that most of the deaths from the virus were among those who were close to death anyway, saying it was effectively “taking months from their lives”.

Predicting that the mortality rate would end up being close to that of “a severe influenza season”, about 0.1 percent, he said he expected the difference in tolls between Sweden and countries that locked down to be “small” in a year’s time.

But this approach has drawn criticism from both at home and abroad, with rising fears over the country’s surging caseload.

Bo Lundback, professor of epidemiology at the University of Gothenburg, was one of a group of researchers who published an open letter to the government urging it to reconsider its approach.

He told AFP this month that the country was “poorly or even not at all prepared”.

One particular concern has been the policies to shield the vulnerable. In early April, authorities said despite measures to protect the elderly, some 40 percent of deaths in the Stockholm region—the epicentre of country’s epidemic—could be traced to retirement and care homes.

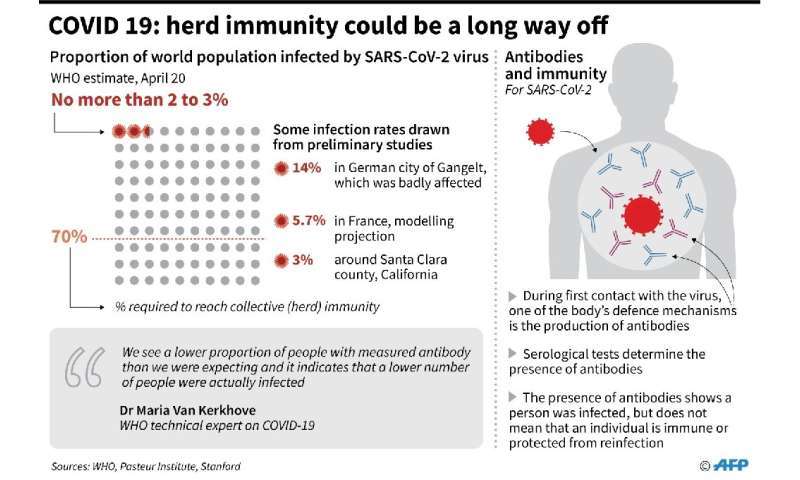

Another point of contention is whether collective immunity will be achievable.

In France, which imposed its lockdown in mid-March, a study by the Institut Pasteur has estimated that only 6 percent of the population will have been infected by May 11—the date slated for its restrictions to be eased.

This is far from the level needed to prevent the epidemic from reigniting, about 60 to 70 percent, according to many experts.

French virology professor Bruno Lina has cautioned that restrictions should be lifted with care to avoid overwhelming hospitals.

But he said periods when the lockdown is loosened could still allow the infection to spread among people aged up to 50 years old, whose rates for very serious infection are “relatively low”.

“If they are immunised, they will end up protecting the whole population,” said Lina.

But that is a big “if”—currently it is not at all clear what level of immunity people who have had the virus develop, or how long they keep it.

As the most obvious European outlier, Sweden is a test case for a looser approach.

Mixed messages

The response in many countries could end up becoming a mixture of lockdowns, testing and tracing efforts and tentative openings that gradually widen the pool of potential immunity.

According to recent study in Science, it will probably be necessary to alternate between periods of confinement and reopening until 2022.

The United States may prove to have the best—and the worst—of all the approaches.

Currently the world’s hardest-hit nation, it has seen a mixture of responses, because of its decentralised system that has seen some states impose strict confinements on their populations while others have resisted.

Economic powerhouse New York, the epicentre of US infections, has imposed a strict lockdown as the virus tears through the population.

But with 26 million Americans made unemployed by the crisis over the last five week, several states have seen pockets of protest against stay-at-home orders.

Eventually, the solution may be “release a little, tighten, release, tighten”, Jean-Francois Delfraissy, who advises the French government on its response, said earlier this month.

Source: Read Full Article