Cancer therapy in recent times relies on the use of several drugs derived from biological sources including different bacteria and viruses, among others. However, these bio-based drugs get easily degraded and therefore inactivated on administration into the body. Thus, effective delivery to and release of these drugs at target tumor sites are of paramount importance from the perspective of cancer therapy.

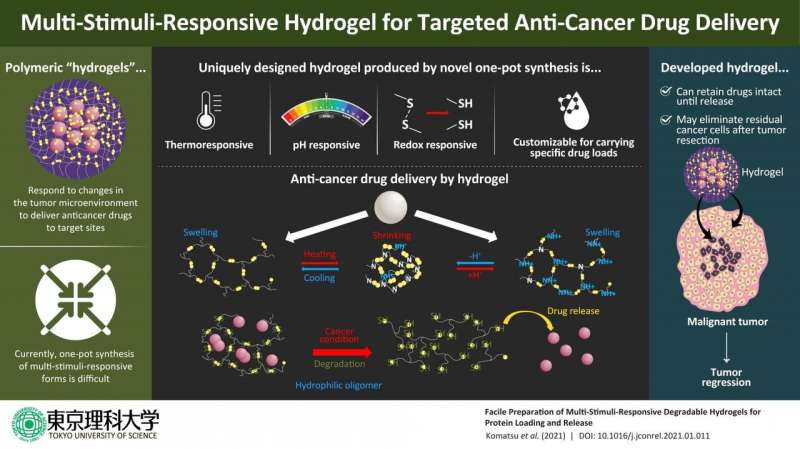

Recently, scientists have discovered unique three-dimensional, water-containing polymers, called hydrogels, as effective drug delivery systems (DDSs). Drugs loaded into these hydrogels remain relatively stable owing to the network-like structure and organic tissue-like consistency of these DDSs. Besides, drug release from hydrogels can be controlled by designing them to swell and shrink in response to certain stimuli, or minute changes in conditions, like temperature or pH (which determines the acidity of an environment). For instance, when conditions are just the right level of acidic in the tumor microenvironment, these DDSs either shrink or swell and release the drug.

However, there has been no method for the one-pot synthesis of hydrogels that respond to more than one such stimulus and degrade to release drugs at target tumor sites. Until now.

Now, a team of scientists, led by Professor Akihiko Kikuchi from Tokyo University of Science, reports the production of unique degradable hydrogels that respond to changes under multiple conditions in “reducing” environments mimicking the microenvironment of tumors. As Prof. Kikuchi observes, “In order to prepare degradable hydrogels that can release drugs in response to changes in the tumor microenvironment, we prepared hydrogels that respond to temperature, pH, and reducing environment, and analyzed their properties.”

In their study published in the Journal of Controlled Release, Prof. Kikuchi—along with his colleagues from Tokyo University of Science, Dr. Syuuhei Komatsu, Ms. Moeno Tago, and Ms. Yu Ando, and his collaborator on the study, Prof. Taka-Aki Asoh from Osaka University—details the steps of designing these novel hydrogels from the synthetic polymer poly(ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether and the sulfur-containing organic compound cystamine. In response to low temperatures, these hydrogels swell up while they shrink at the physiological temperature. Additionally, the hydrogels respond to pH changes by virtue of possessing tertiary amino groups. It must be noted here that the pH of the tumor microenvironment fluctuates between 5.5 and 6.5 owing to glycolysis in the tumor cells. Under the reducing conditions of this environment, the hydrogels degrade because of the breakage of disulfide bonds and change into low molecular-weight water-soluble oligomers that are easily excreted from the body.

To further test their drug release properties, the scientists loaded these hydrogels with specific proteins by exploiting their temperature-dependent swelling-deswelling behavior and tested the controlled release of drugs under acidic or reducing conditions. It was found that the amount of drug loaded onto these hydrogels could be controlled by changing the mesh size of the hydrogel polymer network by changing temperature, suggesting the possibility of customizing these DDSs for specific drug delivery.

Besides, the hydrogel network structure and electrostatic interactions in the network ensured that the proteins were preserved intact until delivery, unaffected by the swelling and shrinking of the hydrogels with pH changes in the surrounding environment. The scientists found that the loaded protein drugs were completely released only under reducing conditions.

Using these hydrogels and the tractability that they provide, doctors may soon be able to design “customized” hydrogels that are specific to patients, giving personalized medicine a big boost. In addition to that, this new DDS provides a way to kill cancer cells that are left behind after surgery. As Prof. Kikuchi states, “The implantation of this material in the affected area after cancer resection may eliminate residual cancer cells, making it a more powerful therapeutic tool”.

Source: Read Full Article