Tens of millions of people worldwide have chronic heart failure, and only a little over half of them survive 5 years beyond their diagnosis. Now, researchers from Japan are helping doctors to assign patients into groups based on their specific needs, to improve medical outcomes.

In a study recently published in the Journal of Nuclear Cardiology, researchers from Kanazawa University have used computer science to disentangle patients most at risk of sudden arrhythmic cardiac death from patients most at risk of heart failure death.

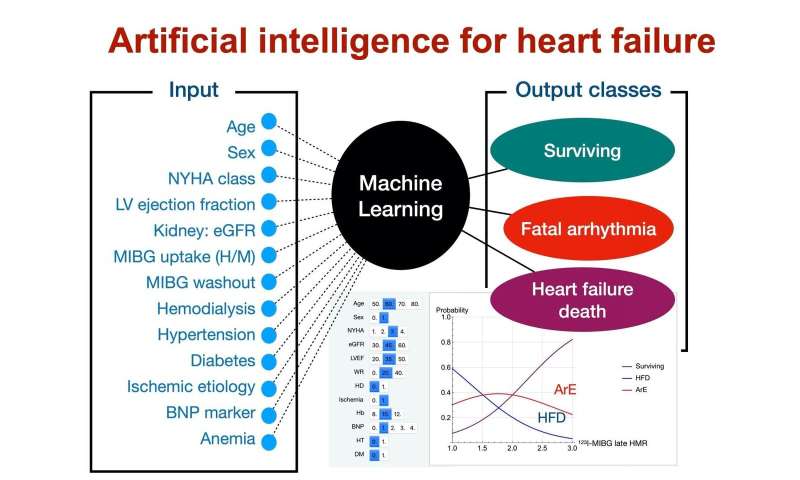

Doctors have many methods at their disposal for diagnosing chronic heart failure. However, there’s a need to better identify what treatment to pursue, in accordance with the risks of each approach. When combined with conventional clinical tests, a molecule known as iodine-123 labeled MIBG can help discriminate between high-risk and low-risk patients. However, there is no way to assess the risk of arrhythmic death separately from the risk of heart failure death, something the researchers at Kanazawa University aimed to address.

“We used artificial intelligence to show that numerous variables work in synergy to better predict chronic heart failure outcomes,” explains lead author of the study Kenichi Nakajima. “Neither variable, in and of itself, is quite up to the task.”

To do this, the researchers examined the medical records of 526 patients with chronic heart failure and who underwent consecutive iodine-123-MIBG imaging and standard clinical testing. Conventional medical care proceeded as normal after imaging.

“The results were clear,” says Nakajima. “Heart failure death was most common in older adult patients with very low MIBG activity, worse New York Heart Association class, and comorbidities.”

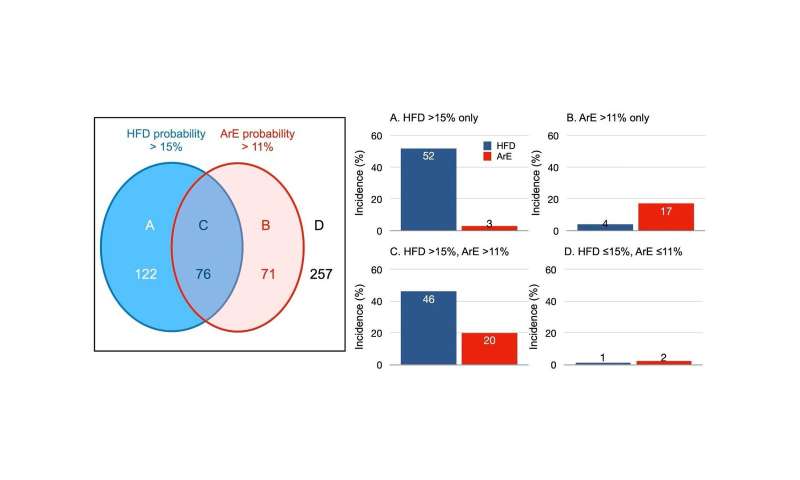

Furthermore, arrhythmia was most common in younger patients with moderately low iodine-123-MIBG activity and less serious heart failure. Doctors can use the Kanazawa University researchers’ results to tailor medical care; for example, the type of implantable defibrillator most likely to meet the needs of the patient.

“It’s important to note that our results need to be confirmed in a larger study,” explains Nakajima. “In particular, the arrhythmia outcomes were perhaps too infrequent to be clinically reliable.”

Source: Read Full Article