Adults talk to babies differently from how we would speak to other adults. Compared to how adults speak, speech directed at babies tends to have a higher, more varied pitch, greater positive affectation, it is slower and involves shorter phrases. The characteristics of this speech targeting babies has been studied extensively and it has been found that it is a common feature of different cultures.

Moreover, several studies have shown that already in the first months of life, babies not only interpret gaze, speech or gestures when we communicate with them, but also understand that other people use them when they communicate.

While previous research has established that babies are sensitive to being spoken to as infants, until now it was not known what expectations children have, whether they expect special speech to be directed at them, and in general for all babies like them, or if they expect adults to talk to each other as adults. A study aimed to find out if babies gain awareness of this conduct and if they can distinguish when someone is addressing them or other adults appropriately.

Animated videos for babies from 12 to 15 months

A study published in the advanced edition of the journal Cognition presents the results of a series of experiments carried out on Spanish and Turkish babies aged 12 to 15 months. The children watched animated videos with big and small geometric figures simulating adults and children talking to each other. The study was carried out by Núria Sebastián Gallés, head of the Speech Acquisition and Perception (SAP) research group at the Center for Brain and Cognition (CBC) of the Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC) at UPF, together with Gaye Soley, a researcher with the Department of Psychology at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul (Turkey).

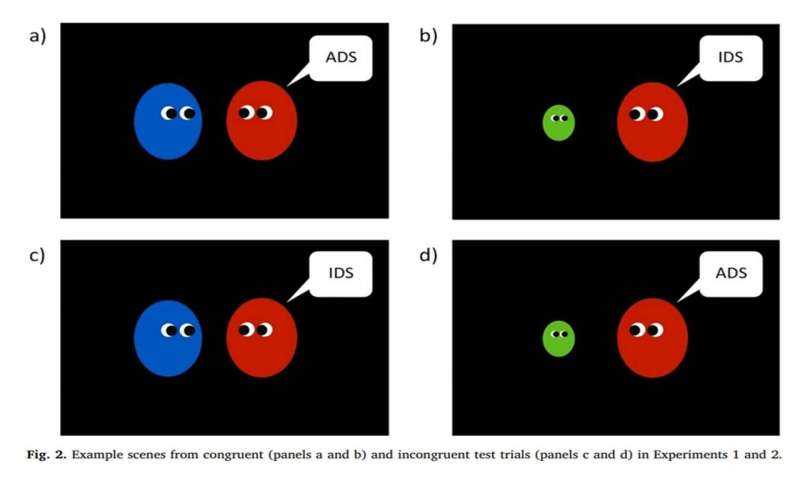

In two of the conditions (Figure 2 a and b of the work), the respective figures communicated congruently, that is, the adult figure addressed the child figure using IDS—infant-directed speech, or another adult using ADS—adult-directed speech. In the other conditions (Figure 2 c and d of the work) this pattern is altered incongruently: the adult spoke to another adult as if the latter were a child, or spoke to the child as if it were an adult. The results showed that both Spanish and Turkish infants aged between 12 and 15 months watched for longer when presented with incongruent than with congruent events. This increased gaze time is interpreted as a reaction of surprise at an unexpected situation.

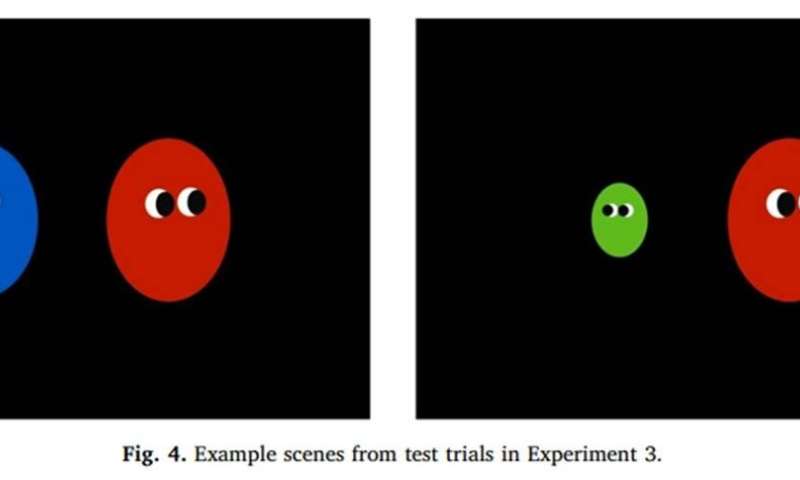

In the last experiment, the stimuli were identical to those of experiments 1 and 2, but the characters no longer ‘looked’ at each other (Figure 4). In this situation, the babies did not show any differences in their gaze time between congruent and incongruent conditions. These results indicate that babies interpret that the figures are not communicating with each other as they do not keep eye contact.

These findings raise important questions about the mechanisms whereby infants’ expectations are formed. “Our results show that infants have formed expectations not only about the recipients of infant-directed speech, but also the recipients of adult-directed speech, suggesting that their expectations are not formed based only on their own experiences, but also on their observations of interactions between adults,” Soley and Sebastián claim.

Babies may develop these expectations as they are exposed to different registers of speech when others around them communicate with babies and adults. If so, infants’ expectations may be different depending on how the adults of their environments produce speech. This could be studied and extended to other forms of communication such as gestures or actions.

Source: Read Full Article