Promoting gamma delta T cell response could be an effective strategy for treating advanced ovarian cancer, according to research by an international team from Karolinska Institutet, Menoufia University in Egypt, and the Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden. Their work has been published in Science Translational Medicine.

There are fewer than 250,000 cases of ovarian cancer in the U.S. each year. However, early stage ovarian cancer is often symptomless, and symptoms that arise in later stages are often nonspecific—nausea, weight loss, or abdominal pain. Further complicating the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer is a common secondary condition called ascites, or accumulated fluid in the abdomen that causes swelling and transports cancerous cells to other parts of the body. For these reasons, ovarian cancer can proliferate undiagnosed until it has spread to other organs (metastasized), at which point it becomes very difficult to treat and is often fatal.

In order to improve any treatment, it needs to be specific to the disease it hopes to combat. Currently, we know that ovarian cancer is often responsive to injections of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIIC) directly into cancerous masses—cancer immunotherapy, for short. But immunotherapy has limited efficacy because we have not fully isolated the therapeutic TIICs that work for different cancers. That’s the focus of this collaborative research, led by Dr. Emelie Foord, Department of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology at Karolinska Institutet and lead author of the study. Speaking to Medical Xpress, Dr. Foord explained the study’s goals and results: “Basically, we looked into a subset of immune cells called gamma delta (gd) T cells. They can have dual roles in cancer,” she explains. “Some … act pro-tumor by the production of IL-17,”—Interleukin 17, linked to many diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis and antitumour immunity. “Others,” she continues, are “important anti-tumor fighters with various important functions including cytotoxicity and helping other immune cells.”

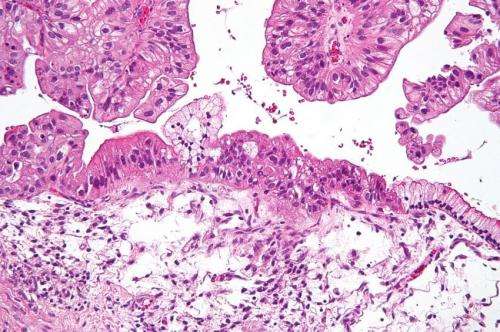

This dual role is one of the complicating factors in cancer therapies; what works for one type of cancer—say, melanoma—could be ineffective or exacerbating in a different cancer such as leukemia or glioblastoma. In order to determine whether promoting a gamma delta T cell response is beneficial or harmful in ovarian cancer, Dr. Foord and her team tested ovarian cancer patients through three samples: blood, ascites fluid, and tumor tissue. The samples then underwent T cell receptor sequencing (TCR-seq), a process that reads the T cell repertoire for specific biomarkers. These results act as a sort of molecular tagging system for which antigens a T cell can identify—and for the purposes of this study, how the samples would react to gamma delta T cell infiltration.

Source: Read Full Article